Early types of Scottish tower house, such as Castle Campbell or the keep at Dunnottar Castle exhibit some qualities of excavated or carved space. Both of these defensive fortifications stand like eroded outcrops of rock on the landscape and appear to be solid and elementary from the outset. The few irregularly placed openings,appear to follow no rules and conceal the internal layout behind the mass of stone. In fact, these seemingly immovable boulders are hollow with walls of varying size up to four metres thick on some elevations. The unusual, indeed incredible size of their walls is an obvious consequence of their task, to be ‘masonry armour’ protecting the grand living spaces within. (Macgibbon 1977)

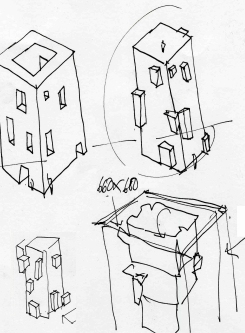

In most tower houses of this same period thick walls enclose an elongated, rectangular or L-shaped plan. The thickness of the walls and their geometry are not readily identifiable, internally or externally. It is only the openings that create a spatial reference to outside and the thickness of the wall only becomes apparent at these reveals. When the openings are placed within the enclosing walls the original geometry of the plan is enforced.

The most interesting spaces occur between the inside and the outside carved within the massive fortified walls. These hidden spaces ‘bore’ through mass allowing light into the interior and are often called ‘poché’ spaces or pocket spaces. Within this ‘inbetween’ layer a diverse range of spatial inclusions can be found, ranging from small chambers, fireplaces, staircases and protrusions from the main rooms to form window alcoves. The space gained in this way allows all the secondary living functions to be transferred into the walls themselves. More often than not the poché spaces have no openings to the exterior in effort to disguise this hollowing or thinning out from the outside.

Casting the Tower House

Thinking about these carved cavity spaces and how they were conceived in sculptural terms suggests a similar king of space making but the result of some sort of inverted casting process, or a Chillida sculpture with a subtractive heaviness, solid space. The architect Luigi Moretti recorded the following sensation when he made his plaster casts of Italian churches:

“interal volumes have a concrete presence on their own account.. as though they were formed out of a rarefied substance lacking in energy but most sensitve to its reception” (luigi Moretti in Tuomey 2004 p46)

Inspired by this notion of capturing solid space I created a series of plaster casts of the tower house at Castle Campbell to explore and quantify the contrasting qualities of mass and volume within a scottish tower house.

The method involved carving out the positive and negative floor plans of the tower house in polystyrene and then fixing them within a timber mould. The plaster was then poured and after hardening the polystyrene was prised out revealing both the positive and negative forms. The final artefacts were interesting when juxtaposed with one another, one being hollow with a lit interior and the other a solid, heavy mass with no interior. This sculptural process of sketching to carving to casting felt richer than building a cardboard model of the tower house, it required thinking in a different way and resulted in an understanding of space and a artefact with both weight and tactility.